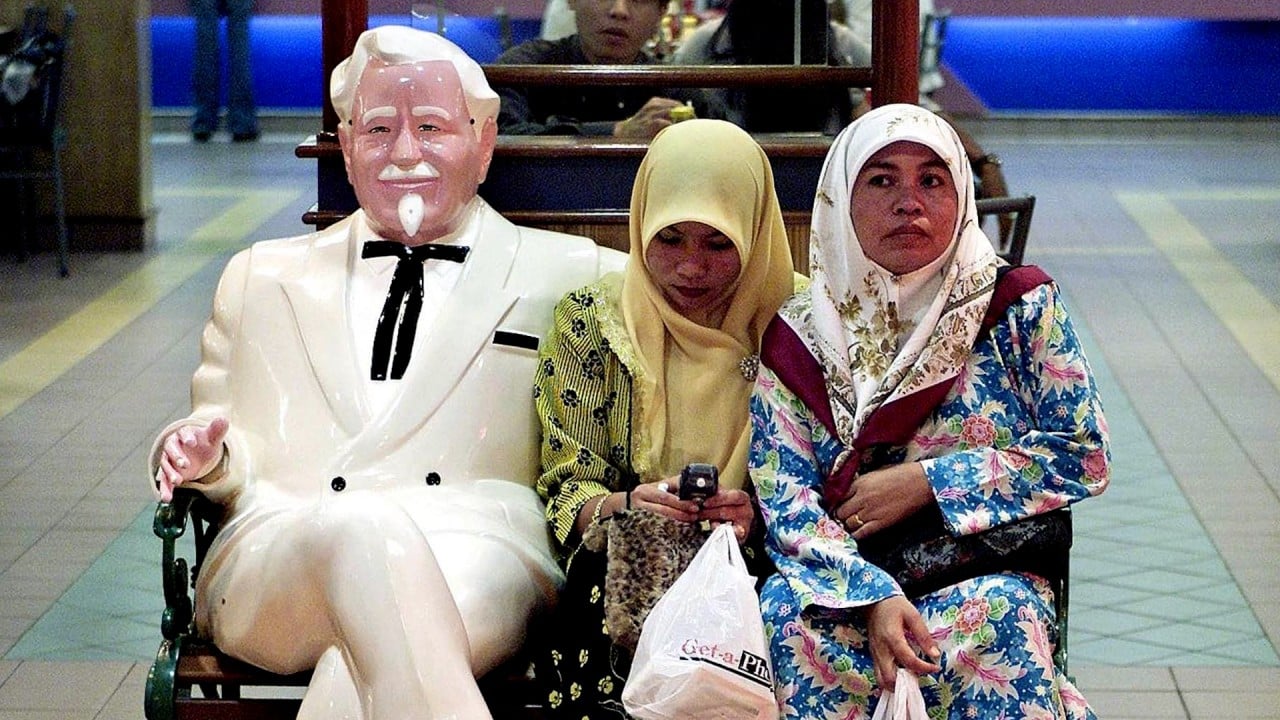

Pro-Palestinian boycotts in Indonesia bite hard into KFC’s bottom line

- Indonesians have also targeted Starbucks, McDonald’s and several clothing brands for boycott over their perceived links to Israel

The operator of fast food giant Kentucky Fried Chicken (KFC) in Indonesia has reported steeper losses as pro-Palestinian boycotts continue to hammer businesses in the country perceived to be associated with Israel or its army.

KFC Indonesia, owned by Fast Food Indonesia, disclosed in a report last week that it recorded a net loss of some 348.83 billion rupiah (US$21.5 million) in the first quarter of this year, a jump of more than 60 times from a loss of 5.56 billion rupiah (US$343,825) in the same period last year.

In the city of Medan, the provincial capital of North Sumatra, a KFC manager told This Week in Asia that he was “unsurprised by the news but surprised the losses were not higher”.

The manager, speaking on condition of anonymity, said he had noticed a sharp downturn in business since November last year following the outbreak of the war in Gaza in October.

“It is the result of the boycotts because of Palestine. The restaurant is very quiet from Monday to Thursday.”

The boycotts across Indonesia first took hold at the start of the war when McDonald’s Israel was reported on social media to have handed out free burgers to members of the Israeli military.

In the months that followed, the boycotts also targeted other brands seen as “pro-Israel” including Starbucks and McDonald’s.

In a move to entice more customers, the KFC manager in Medan said that the fast food chain’s Indonesian franchisee has started running more promotions and discounts.

“At the weekend, we still have some customers, but usually they only come if we have a promotion running,” he said.

One former KFC customer who is enticed by those promotions is Ade Andriany, a doctor based in Medan. She told This Week in Asia that she has refused to frequent the fast food chain with her young family.

“We don’t buy KFC any more because of the boycott but if it is a friend’s birthday party or a children’s event, then my children are still allowed to eat KFC because it is halal. It is just that we don’t buy it as a family any more,” she said.

“We haven’t bought it since the start of the war and our children don’t want to eat it either. If anything, the children are more vocal about it than we are,” she added.

To replace KFC, the family now buys fried chicken from Singaporean fast food chain 4Fingers Crispy Chicken and the Indonesian-owned Richeese Factory.

Andriany said that her family’s boycott extended to Starbucks, McDonald’s and several clothing brands.

“I was looking for a jacket for an event for my 11-year-old son and he immediately said ‘Don’t go to Zara, Mum, their money is used by Israel to attack Palestine’,” she said.

KFC is one of the oldest and most beloved fast food outlets in Indonesia. It has deep roots in the country, where 87 per cent of the 270 million population is Muslim.

The first KFC opened in Indonesia’s capital city of Jakarta in 1979 and, according to its website, there are 739 outlets across Indonesia, spanning 150 cities.

Arie Parikesit, a culinary guide behind the Kelana Rasa food tour company, said when KFC first opened in Indonesia in the 1970s, it still used the same menu as the US branches, with offerings such as fried chicken, fries, mashed potatoes, coleslaw and corn on the cob.

“But not all the menu items were suited to the tastes of most Indonesians and, little by little, some were removed and new ones added. Adding rice, chilli sauce and crispy fried foods was the key to KFC winning the hearts of Indonesians.”

KFC also replaced its original chicken with a more popular crispy chicken variant, something copied by other fast food outlets like McDonald’s, which also added chicken and rice to its menus to appeal to the Indonesian palate, Parikesit added.

McDonald’s opened in 1991 and has 269 outlets across the country.

In an attempt to mitigate the impact of the boycotts, KFC Indonesia commissioner Achmad Baiquni said in November last year that the company and all employees expressed deep concern for the plight of Gazans, particularly women and children.

The company also made a 1.5 billion Indonesian rupiah (US$97,764) donation to the Indonesian Red Cross to assist the latter with its work in Palestine.

“It is hoped that the donation we are providing will help and lighten their burden in facing the current very uncertain situation,” Baiquni said in a statement then.

Ega Kurnia Yazid, an economist at Indonesia’s National Team for the Acceleration of Poverty Reduction (TNP2K), told This Week in Asia that the impact of the boycotts could be measured by the drop in share prices of products affiliated with Israel and the US and the financial performance of these companies.

In Malaysia, coffee chain Starbucks, owned by Berjaya Food, reported a 38.2 per cent decrease in revenue in the fourth quarter of last year, which it “attributed to an ongoing boycott”.

In February, the head office of McDonald’s US said that international sales rose only 0.7 per cent during the fourth quarter of 2023 compared with a 16.5 per cent gain the previous year, which McDonald’s CEO Chris Kempczinski blamed on “countries like Indonesia and Malaysia”.

In April, KFC Malaysia also temporarily closed more than two dozen outlets in the Muslim-majority states of Kelantan, Kedah and Terengganu.

Yazid noted the ongoing boycotts came with risks and did not just affect the companies targeted.

“There are side effects that may have a negative impact on the local economy, namely the negative effect on sales of micro, small and medium enterprises that serve the distribution of Israeli-American affiliated products,” he said.

At another KFC outlet in Medan, the branch manager also said that his restaurant had noticed a significant slowdown in the number of customers.

“Customers have been influenced by social media and think that KFC Indonesia is sending money directly to Israel to take part in the war ... when actually we are a franchise, source all our ingredients locally in Indonesia and employ an all-Indonesian staff,” he said.

In the Indonesian city of Solo, management consultant Indrawan, who used one name like many Indonesians, told This Week in Asia that he was also boycotting KFC and other Western food and beverage outlets.

“I have been boycotting KFC because their money supplies the robbers of Palestinian land,” he said.

“There are many other local brands that offer alternatives like Rocket, D’Kriuk, Saban and Hisana. Local fried chicken is more tasty than KFC anyway and I know most of the owners of the local outlets personally.”

Like Andriany, Indrawan said he had to compromise whenever he met friends who chose not to boycott perceived Israel-affiliated brands.

“At the end of last year, a friend of mine invited me to have a drink with him at Starbucks,” Indrawan said.

“I went to meet him because I didn’t want to be rude, but when we left I said ‘This is the last time I’m going to come here, and I hope it will be the last time you come here too’.”