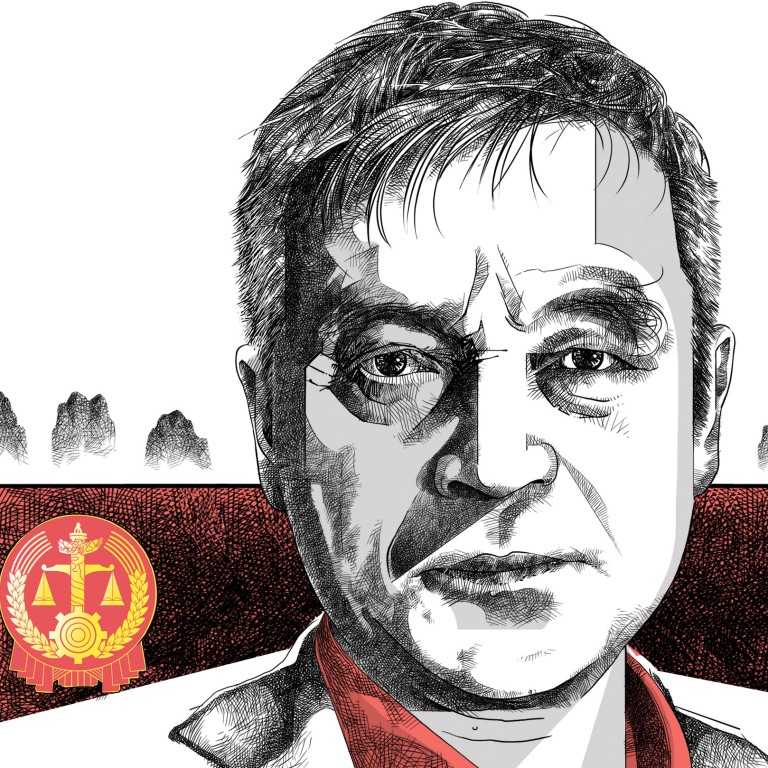

Open questions | In the name of the law: scholar He Weifang argues his case for remembering China’s past

- The retired academic speaks out about his country’s legal system, the Cultural Revolution, private enterprise protection, nationalism and why 2008 was China’s ‘first year’

You retired last July, bidding farewell to your fruitful career as a legal scholar. How is life after retirement and do you still have some work to do?

It’s quite good. I still have three PhD students under my supervision who have not yet graduated.

I supervised a concentration in Western legal history, which is more historically oriented. Some of my students specialise in the different versions of the Magna Carta that evolved, some study the early development of the legal profession in England, and some study how the common law adapted to the 13 colonies as a “New World” environment prior to the founding of the United States.

I encourage students to do such studies because they help people understand how the rule of law works. They do not necessarily have to relate to the reality of China.

I am happy to say goodbye to the classroom at this moment, because university teachers now face more difficulties. My discipline is law and constitutionalism, and my comments on current affairs have often been at odds with the authorities.

You have been teaching at universities, including the China University of Political Science and Law and Peking University, for almost 40 years. Looking back, was there a moment you were especially proud of?

I am particularly convinced that what I study and teach is an extremely important discipline for the future of China.

More than 2,000 years of governance in ancient China has given us the impression that the Chinese legal system has a significant “genetic defect”.

So I think my life has been fulfilling because I have been able to think about China’s future based on historical comparisons between Chinese and Western legal systems, which is also meaningful for our mission to rebuild the Chinese civilisation.

At Peking University Law School, I was voted the best teacher many years in a row, as well as the best teacher in the entire university. These honours have also made me proud.

How has China’s legal system changed during your long career? What are your views on how China should promote the rule of law?

Legal practitioners of my generation are eyewitnesses to history and have seen this country go from having almost no laws to having many new kinds of laws.

When my generation was in college, in 1979, China enacted its criminal law and criminal procedure law. They were the first laws after the reform and opening up. Later, China introduced the administrative litigation law and the general rules of civil law. Laws are being drafted more frequently.

There was also a lot of legislation that did not follow the spirit of the rule of law. Nevertheless, China has established the direction of “law-based governance”, which was exciting for us.

For a long time, we legal scholars had a good relationship with the courts and procuratorates. When they made new rules, they would hold meetings to listen to our views.

I personally participated in the revision of the Organic Law of the People’s Courts, but it failed in the end. What a pity!

That was in 2004, when I drafted an almost new 50-article proposal. At the end of that year, The Beijing News heard about our draft law and interviewed me, but it caused a huge uproar.

Our proposal was to remove the word “people” from the name of the “People’s Court”.

This seemed to outrage the leadership, and it became almost an ideological debate over whether to keep “the people” or not.

In the end, our proposal did not work. After that, I became more and more “sensitive”.

I was also keenly aware that it was impossible to separate changes in the legal system from reforms in the political system and ideology. The so-called question of “which is more important, the party or the law” cannot be resolved.

Many things happened in the next few years, and then it was 2008.

Looking back, I have realised that the year 2008 was the beginning of many political changes that followed in China, a “first year” in a sense.

You have been speaking out about the need to pay attention to the history of the Cultural Revolution all these years. Why is this so important for the Chinese people?

It’s important that the party has completely repudiated the Cultural Revolution. But I find it rather sad that it has also banned the study of the Cultural Revolution, making it a forbidden zone.

As a result, many people of the next generations simply do not know what the Cultural Revolution was about.

So even though I no longer have much room to speak out, I am still trying to find ways to remind people.

But I did not at all expect the direction China has taken since then.

In terms of political reform, I think the last window for China was when Deng Xiaoping was in power, the mid- to late 1980s, but the transition did not happen, and it became even more difficult afterwards.

The communists of Deng’s generation believed that economic development would inevitably bring about a change in the political system.

Over the past two years, the top leadership has repeatedly emphasised the need to protect private enterprise. You have also stressed this many times. Why do you think this is important?

Because in order to maintain a good market economy, the government must strictly protect citizens’ property rights, business freedom and freedom of contract.

If a place does not have a solid guarantee of private property and transaction security, it cannot have a rule of law, nor can it have a good guarantee of human dignity.

So in China, if there is no solid rule of law to go with the market economy, and if the capitalist class does not feel that there is real stability, they will always be very nervous.

The problem now is the regular appearance of huge fines and other punishments in the absence of public hearings and fair trials. In a place where there is political rationality and the rule of law, property cannot be taken away so easily and serious hearings and judicial decisions are required.

You cannot say that sometimes you deprive a group of people of their property and sometimes you want to calm them down. This repetition will not solve any problem.

I think it is better to start at the root. For example, the protection of private property should be improved and firmly stated in the constitution.

You have been teaching at law school for 40 years and have trained many famous Chinese lawyers and legal scholars. Based on your observations, how have students’ concepts of law changed over the decades?

One is that the study of law is gradually deepening. When I was a student, law books were incredibly poor. But now students read more broadly and more deeply. So I think students who have graduated in recent years have a much better understanding of the law.

The difficulty is how to really bring the pros of the Western legal system to China to solve China’s problems.

Academics need to respond to the challenges that arise in legal practice, and the new theories that emerge from these challenges need to be tested and enhanced in practice. It is a virtuous cycle.

The problem in China, however, is that some of the major cases that have received widespread attention have not been conducted with basic fairness in the judicial process.

For those studying law, such a reality is some sort of corrosion and quite a frustration. Some students may feel that what they are learning is a luxury or even taboo in this country.

So over the years I have sensed powerlessness among university teachers and students.

In terms of political attitudes, some of my younger colleagues have embraced nationalism and some have even harboured strong nationalist sentiments. And some young academics themselves have become increasingly anti-Western.

In the 1980s and 1990s, at the beginning of your career as a university teacher, were college campuses more ideologically liberal than they are now?

Yes. The Cultural Revolution had just ended, and everyone was reflecting on the lessons of that history. There were still vivid memories of the tragic events and human rights traumas during that decade-long catastrophe.

So the problems we have just been talking about did not exist then. Moreover, China’s relations with the West were in a “honeymoon” after the start of reform and opening up.

In the last decade or so, the voice of public intellectuals in China seems to have declined and even been defamed. Do you think the decline is due to policy changes, or is it due to changes in people’s minds?

It’s entirely the result of silencing by the authorities.

In 2011 or so, when there was the most discussion about public events on Weibo, I had 1.87 million followers. Then I was silenced for a month or three months, the longest being 108 days, for the slightest criticism of the authorities. In the end, my account was completely blocked, and there was no room for any public speech online.

I published many articles in the media before, but in the end I was not even allowed to publish them under my pseudonym.

It’s about silencing your voice.

Public intellectuals are also subject to criticism in Western countries. But it is crucial that you can hold on to your principles when you are being criticised and continue to do what you believe is valuable.

As an active public intellectual, you were often involved in international exchanges, including meetings with the leaders of some major powers, such as Angela Merkel of Germany. You have also made regular academic visits to the United States, Japan and other countries. What is the value of such international exchanges for Chinese intellectuals?

This kind of two-way exchange is especially important. Our observations of Western systems are not accurate unless we are there in person. Exchanges with our counterparts in Western universities are also important.

Western scholars also need interaction to understand China. It is clear, however, that such communication is becoming more difficult.

Do these statements of yours – criticising the authorities – contravene your party membership?

There is no contradiction. An organisation with almost 100 million members cannot be one-sided. Mao Zedong said in his time that “it is feudal to believe that there is no party outside the party, and it is strange that there is no faction within the party”.

Of course I am a party member, but I do not think that this identity is more important than my identity as a scholar.

I am first and foremost a professor of law, and I must use the knowledge and logic of law to analyse social problems and make my own suggestions or criticisms, which is the role of a scholar and does not conflict with my role as a party member.

If China’s legal system is not moving in the direction that you expect, what direction do you think Chinese lawyers, or legal scholars and students like you, can pursue and what are the obstacles?

Personally, I don’t want to take myself too seriously in the current situation, and there are still lots of fun things to do. If you are not in a hurry to put your ideals into practice, then sit down and wait for the dawn. For example, in recent years I have returned to history books.

But young academics today are in trouble. They are under pressure to publish papers, and they have to undertake a variety of national research projects. The topics of these projects are too ideological and political now.

Under such circumstances, it does not seem easy to adapt and build up one’s reputation in academia.

But I think there should still be a sense of hope. Something regressive does not necessarily last too long.

Do not believe that the Yellow River and the Yangtze River will not flow backwards, they do sometimes, but in terms of the general trend they are still flowing eastward.