Could China gain from Vietnam’s political infighting and ‘hardline’ tilt?

- Vietnam’s ‘blazing furnace’ anti-corruption campaign has claimed a number of senior figures, turmoil that one analyst says is unprecedented

- The cracks in the leadership may affect the ruling party’s ability to stand united to deal with China on the South China Sea dispute, observer says

The country’s former minister of public security To Lam, who is widely seen as playing a central role in the political upheaval, has been appointed president and is in a prime position to succeed Trong in the next leadership transition, along with Prime Minister Pham Minh Chinh.

While the anti-graft drive has proved popular with the public, the expanding crackdown – which ensnared thousands of people, including top officials and senior business leaders – came as Vietnam sought to benefit from the diversification of Western investment away from China.

China is expected to benefit from Vietnam’s unprecedented political turmoil amid months-long infighting and internal machinations within the ruling Communist Party, and signs of a more authoritarian tilt in Hanoi, according to observers.

Bill Hayton, an associate fellow at the Chatham House Asia-Pacific Programme, described the turmoil as “unprecedented” and said it showed politics in Vietnam was “in a permanent state of flux”.

“We do not know if this is the end of the fight or a kind of halfway stage,” he said. “At the moment, it looks like the hardliners, notably the police generals and the Leninists, have won the battle.”

Aside from Lam’s rise, General Luong Cuong, 67, director of the General Department of Politics of the Vietnam People’s Army, was promoted to replace Truong Thi Mai at a plenary session of the Central Committee on May 18. The party also named four new members to the Politburo last month.

The intense power struggle might have a far-reaching impact on the country’s future development, as the new Vietnamese leadership appeared willing to “sacrifice some economic growth in the interests of tighter political control”, Hayton said.

“This is probably going to slow down Vietnam’s integration into the world, as Vietnam looks set to follow China in a political inward turn, focusing more on political security and regime survival than economic development,” he said.

Beijing, which has watched Vietnamese politics closely, would be pleased to see the personnel changes, according to Hayton.

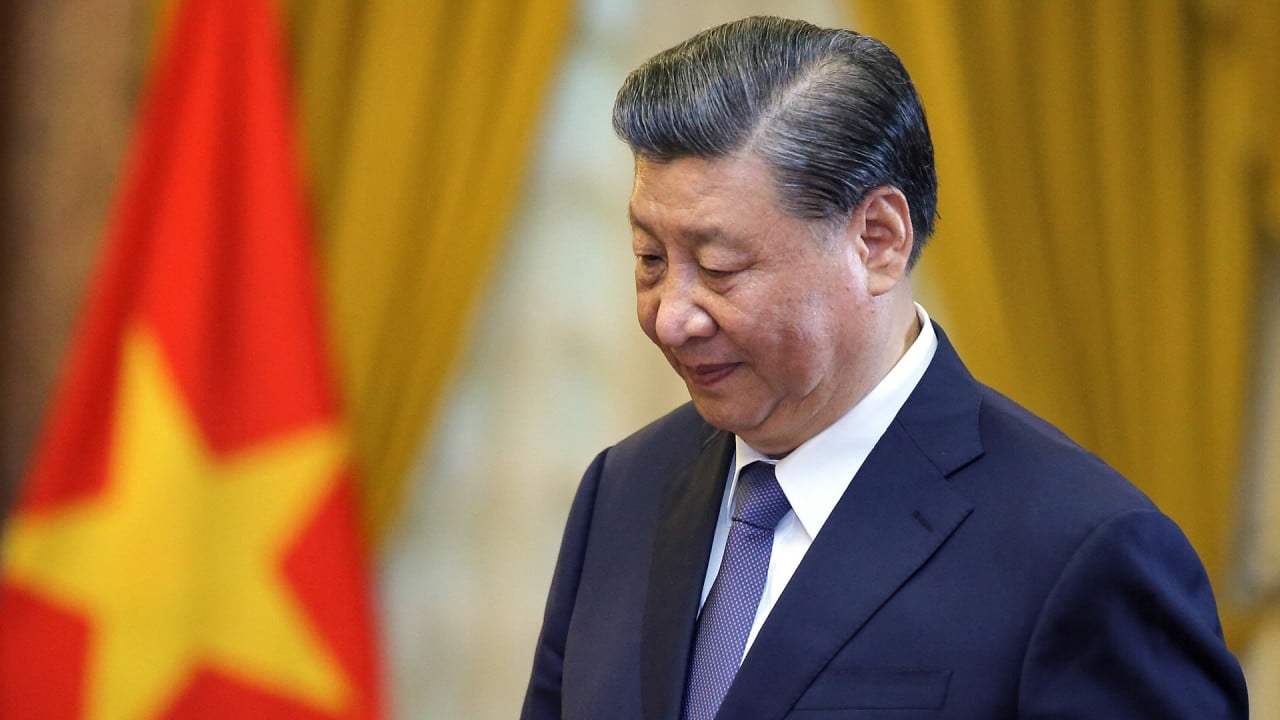

“This is exactly what they [Chinese officials] want. They want a kind of hardline group politically thinking the same way as [President] Xi Jinping and China and much more sceptical about the West, following a lot of Chinese hardline policies, copying the anti-corruption campaign and closing down access to information for outsiders,” he said.

With the people in power becoming more suspicious of the United States and its role in promoting democracy and openness, Hayton said Vietnam was likely to turn away from the US.

“It becomes obvious that they have a pro-China leadership. Vietnam will claim they are still neutral and their policy remains unchanged. But it’s going to be a more authoritarian leadership that will find it more difficult to work with the West than China and Russia,” he said.

Zhang Mingliang, a regional affairs specialist at Jinan University in Guangzhou, noted the emergence of several factors that favour Beijing in the unusual political shake-up in its Southeast Asian neighbour.

“There are few signs that the infighting is already at its peak, and it is expected to continue and may become more intense in the lead-up to the 2026 transition. It shows the cracks in Vietnam’s top leadership, which may affect the ruling party’s ability to stand united to deal with China on the South China Sea dispute and other issues,” he said.

“For China, Vietnam has always been a thorn in its side. But the spiralling political turmoil may distract the leadership in Hanoi, making it more difficult to seek unity on external issues, which could weaken its policy towards China and thus benefit Beijing,” he said.

In Lam’s inauguration remarks shortly after he became Vietnam’s third president in less than two years – his two immediate predecessors resigned for “violations and wrongdoing” – he vowed to “resolutely and persistently continue the fight against corruption”.

Instead, Lam focused on the party’s leadership and control, pledging to “strengthen order and discipline” and resolutely “prevent and repel ‘self-evolution’”, which according to Hayton refers to the tendency of individuals to place themselves ahead of the party.

According to Zhang, Lam’s ideologically-focused, combative remarks underlined Hanoi’s priorities of political stability, which could be achieved only through close cooperation with Beijing.

“With consolidating the party’s control and safeguarding the system becoming a rallying cry within the ruling party, it is likely that Vietnam will keep a distance from the West. That’d be good news for China too,” he said.

Carl Thayer, emeritus professor at the University of New South Wales in Australia and a Southeast Asia specialist, said the leadership turmoil was unlikely to affect Vietnam’s foreign policy and its balancing act between Beijing and Washington.

“Vietnam has been on a steady course of diversifying and multilateralising its foreign relations for more than three decades. Vietnam has and will continue to go out of its way to develop all-round cooperative relations with its partners, especially its seven top-tier comprehensive strategic partners: Russia, China, India, South Korea, the US, Japan and Australia,” he said.

“One indication of Vietnam’s balancing act is that as Chinese exports to the US decline, Vietnamese exports to the US increase based on a rise in Chinese exports to Vietnam.”

Former president Thuong – Trong’s protégé and the youngest member of the powerful Politburo – visited China twice last year in a bid to ease Beijing’s concerns about Hanoi’s warming ties with the US, Japan and their allies amid their widening rift over the maritime dispute.

Nguyen Khac Giang, an analyst at Singapore’s ISEAS-Yusof Ishak Institute, also played down the impact of the political turbulence at the top on the general direction of the country.

“Vietnam has gradually become more authoritarian, but its open economy and multilateral foreign policy prevent it from becoming an inward-looking state,” he said. “While the turmoil might distract Vietnam’s efforts in addressing the situation in the South China Sea, I don’t think it will change its current approach.”

But Zhang also cautioned that Beijing should remain vigilant because excessive infighting and struggles for power could undermine Vietnam’s political stability and “an unstable Vietnam would not be a blessing for China”.

However, he said, external factors, such as possible incidents with Beijing in the South China Sea, could disrupt Sino-Vietnamese ties and push Hanoi closer to Washington’s orbit again.

Hayton also said Beijing should tread carefully in handling the maritime row with Hanoi.

“In some way, that’s the one issue where China is shooting itself in the foot, because China takes such a hardline attitude towards the South China Sea and does not recognise the validity of other countries’ claims. That undermines the communist leadership in Vietnam,” he said.

He suggested that “if China wanted to be smart, it would find a compromise with Vietnam and that would make the position of its friends in Hanoi much more secure”.

“Anything that sees the leadership as unpatriotic or being too subservient to China would be a major cause against them. So if Vietnam suffers any humiliation from China in the South China Sea or other areas, it’d be an excuse to act against the leadership and cause a backlash, and that would probably go against what China’s real interests are,” Hayton said.

While the political turmoil raised concerns among countries abroad about the real motivation behind the anti-corruption drive, they are certain of one thing: it has not come to an end.

Zachary Abuza, a Southeast Asia expert and professor at the National War College, in Washington, said it was the most politically turbulent period of Vietnamese politics in history.

“[Lam] has weaponised anti-corruption investigations to systematically eliminate his political rivals,” Abuza said.

Lam has manoeuvred to become the country’s next top leader when the 80-year-old Trong is expected to retire at the party’s five-yearly congress in early 2026.

“That clearly dents the country’s selling point to foreign investors, that it offers political stability and predictability. But Vietnam’s political system is based on collective leadership, so that gives them a degree of resiliency,” he said.

“The infighting, however, is not over, and I expect more heads to roll before the 14th [party] congress, expected in January 2026.”