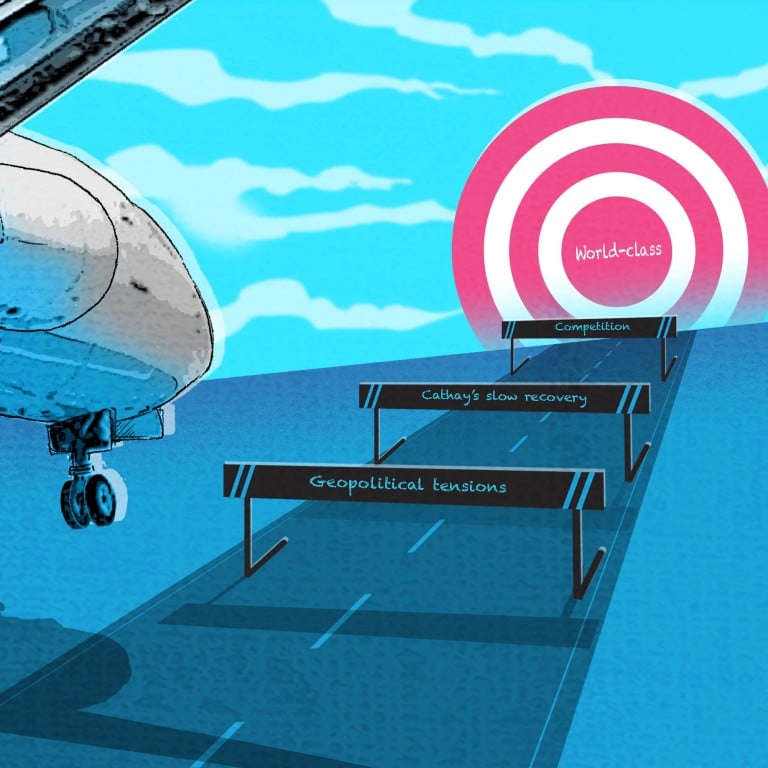

Are Hong Kong’s aviation hub ambitions hampered by Cathay’s pilot shortage, capacity issues?

- Three-runway system in Hong Kong will boost capacity, but fast-growing Shenzhen and Guangzhou airports step up pressure

Hong Kong Airport Authority chairman Fred Lam Tin-fuk had his work cut out for him when he took a delegation to Beijing early last month.

Beijing’s point man on Hong Kong affairs, Xia Baolong, told him the authority running the airport would have to capitalise on its unique advantages under the city’s “one country, two systems” governing principle and continue contributing to national development.

Lam, newly appointed, promptly pledged to make the best use of “enjoying the strong support of the motherland and connecting closely to the world”.

The airport is on track to open its HK$141.5 billion (US$18 billion) three-runway system by the end of this year, boosting capacity by half to 120 million passengers and 10 million tonnes of cargo annually. In comparison, Singapore’s Changi Airport currently can handle 85 million passengers a year.

The airline has pushed back its target for restoring full pre-pandemic capacity from year’s end to the first quarter of 2025, a delay especially critical because the new three-runway system will be ready and waiting for passengers and cargo.

Urging the airline to do its utmost to speed up recovery, transport minister Lam Sai-hung warned that Hong Kong might have to turn to other airlines to take up the added capacity.

Critics also pointed to growing regional competition from mainland Chinese airports, the exit of some foreign airlines and continuing US-China geopolitical tensions as challenges dogging Hong Kong airport.

To stay ahead, they said local airlines – especially Cathay, the only local premium carrier – had to woo customers by offering better service with greater connectivity. Otherwise, Hong Kong could lose out.

Mishaps a setback, signs of recovery

On the surface, the airport appeared on track for robust growth as it staged a strong post-pandemic recovery, bouncing back to a net profit of HK$1.61 billion in 2023-24 after three straight years of losses.

However, that was well below pre-pandemic levels, at about 27.5 per cent of the HK$5.86 billion reported in 2019-20.

The airport handled 45.2 million passengers in 2023-24, under three-quarters of the 2019-20 level. It handled an average of 5,955 flights per week.

Back-to-back mishaps in June which resulted in chaos also put the spotlight on the airport’s contingency planning capabilities.

Experts said such incidents hurt Hong Kong’s reputation as an aviation hub, despite reclaiming its position last year as the world’s busiest cargo airport and the Asia-Pacific’s fourth busiest passenger airport after Changi, Seoul Incheon and Bangkok.

Shenzhen Bao’an International Airport is adding a third runway costing 12.3 billion yuan (US$1.76 billion), expected to be completed next year. It is projected to boost the airport’s capacity to 80 million passengers and 2.6 million tons of cargo by 2030.

Guangzhou Baiyun International Airport is building a fourth and fifth runway to be ready by next year, making it the world’s largest single airport, able to handle more than 120 million passengers a year.

As of the end of last year, it offered services on more than 100 international and regional routes, including to Los Angeles, Rome, Paris, London, Sydney, and Port Moresby, operating more than 1,000 flights a week.

Law Cheung-kwok, senior adviser at the Chinese University of Hong Kong’s Aviation Policy Research Centre, said the Shenzhen and Guangzhou airports were designated by Beijing as international hubs, putting the city at a disadvantage when it came to airfares.

“Now the three airports – Hong Kong, Shenzhen and Guangzhou – run six long-haul flights to Amsterdam, Dubai, Frankfurt, Los Angeles, Paris and Sydney and also run similar short-haul services,” he said.

“If local fliers think the city’s airfares are too expensive, they can simply fly from Shenzhen to these destinations. The competition is already there and the rivalry will be even more intense in the future among the three airports.”

To stay ahead, Law said Hong Kong authorities had to secure more air traffic rights with other countries to expand the city’s connectivity and local airlines had to shape up on service.

“Shenzhen has recently rolled out direct flights to Mexico City whereas Hong Kong still hasn’t any direct service to South America,” he said.

But he felt the rising regional rivalry would be good for the overall economic growth of the Pearl River Delta and would not undermine Hong Kong’s interests.

An aviation industry insider was confident Beijing would ensure that Shenzhen and Guangzhou would not be a major threat to Hong Kong’s aviation hub ambitions.

“Beijing won’t allow Shenzhen to run too many international routes because many are loss-making, requiring a lot of mainland government subsidies,” the source said. “After all, Beijing has designated Hong Kong to play the role of a world-class aviation hub.”

Lawmaker Jeffrey Lam Kin-fung, a member of the city’s key decision-making Executive Council, argued that Shenzhen was no match for Hong Kong.

“Shenzhen hasn’t become an international aviation hub yet whereas Hong Kong should continue to maintain its status as a global air hub,” he said.

“The two places should serve as partners or brothers to complement each other through cooperation in the Greater Bay Area, not as competitors.”

He agreed that Hong Kong had to do more to expand traffic rights to airlines other than Cathay, to optimise the increased capacity when the three-runway system began operating.

Carrots to lure back airlines

According to data from aviation analytics company Cirium, 86 airlines operated services in Hong Kong in July 2019, before the Covid-19 pandemic brought international air travel to a halt.

Today, only 71 airlines operate out of the airport. Among the 26 that stopped services during the pandemic and have yet to resume are American Airlines, Virgin Atlantic, Aero Nomad Airlines, Mandarin Airlines, All Nippon Airways, Virgin Australia, Thai Smile and Air Seoul.

Eleven airlines have started flying through Hong Kong, including Greater Bay Airlines, Loong Air, Starlux Airlines, Hainan Airlines and Qingdao Airlines.

To lure back airlines that had not yet returned or nudge existing ones to increase services, the Airport Authority began offering a subsidy of up to HK$7 million a year to those that start a new daily route.

Five airlines added a total of eight destinations since the scheme began on June 1.

The carriers are HK Express, Cathay’s budget airline, Taiwan’s Starlux Airlines, China Southern Airlines, Hong Kong Airlines and Jin Air of South Korea.

The new routes are to Kashgar, Xining and Harbin in mainland China, Taipei and Taichung in Taiwan, Seoul in South Korea, Da Nang in Vietnam, and Clark in the Philippines.

Subhas Menon, director general of the Association of Asia-Pacific Airlines, said having more overseas carriers running new routes or services with the opening of the three-runway system would create healthy competition and boost the city’s air hub development.

“If there is more competition and more destinations with different price levels, it’s better for consumers because they have a choice,” he said.

“So from our perspective, it’s healthy competition. With the new runway, airlines can have more slots, overseas airlines can compete in Hong Kong.”

He did not think Cathay’s interests would be hurt, given its dominant position in the city. “Cathay is very important for Hong Kong’s economic health,” he said.

Cathay’s misjudgment over pilots?

Responding to the Post, Cathay said it had experienced the most challenging period in its history after being subjected to some of the world’s most restrictive policies during the pandemic.

“We will continue to develop our global network; so far this year, the Cathay group has already announced 10 new destinations, seven of which have commenced services with Ningbo, Riyadh and Cairns set to follow over the coming months,” it said.

“As the local airline, we are a key contributor to the future success of the international aviation hub,” Cathay group chairman Patrick Healy said.

“Our substantial investments further demonstrate our unwavering commitment to fostering Hong Kong’s ongoing economic development.”

The company revealed that it would buy 30 aircraft on top of the previously ordered 70 as part of its investment drive, taking total orders to more than 100.

The carrier said it welcomed competition and recognised that an active and vibrant market for air services was critical to the success of Hong Kong as an international aviation hub.

The airline, flying to more than 80 destinations worldwide, accounted for more than half of Hong Kong airport’s passenger throughput last year, carrying more than 20 million people. It also delivered a fifth more cargo at 1.38 million tonnes last year compared with 2022.

Some blame Cathay’s slow recovery for stalling the airport’s development, saying its manpower crisis is the result of miscalculation during the pandemic years.

The aviation insider said Cathay made a wrong move by sacking 1,000 pilots in 2020, without considering how to get them back when global aviation revived and the third runway opened.

Drastic pay cuts led to another 1,000 resigning over the next couple of years, according to the Hong Kong Aircrew Officers Association (HKAOA), which represents Cathay pilots.

Cathay must hire another 300 pilots to meet its revised target of reaching pre-pandemic capacity early next year. Even that number would boost the total to 3,400, still 400 fewer than in early 2020.

In comparison, rival Singapore Airlines restored capacity faster because most of its pilots stayed on by accepting pay cuts during the pandemic. Cabin crew who switched to temporary jobs in other sectors also returned to flying.

HKAOA chairman Paul Weatherilt said Cathay misjudged the impact of cutting pay permanently for frontline staff.

“Experienced pilots continue to resign, though at a reduced rate. These experienced pilots have found a welcome elsewhere amid a global shortage,” he said.

New hires had to be trained and this would also affect the airline, he stressed.

“Even when it does recover to pre-pandemic capacity, the airline will be too small to support government targets for the Hong Kong aviation hub,” he added.

Frederick Yip, executive director of travel agency Goldjoy Group and a member of the government’s aviation development and three-runway system advisory committee, said despite “hiccups” such as the manpower crunch, Hong Kong airport had ample room for growth.

He said it was being transformed from a city airport into an “Airport City” through the rigorous expansion of its core passenger and cargo services, multimodal regional connectivity, retail, hotels and commercial developments.

Projects under the Airport City vision include the three-runway system, large-scale integrated facilities, hotels, offices, logistics centres, exhibition centres and transport infrastructure that will be integrated to form a commercial landmark.

“Hong Kong was the last place to reopen itself [after the pandemic] and we are catching up very quickly. But give us a bit of time and we will be able to restore full capacity,” he said.

He said the airport was also keen to strengthen its cargo services and its position as a logistics and transit hub.

“I have full confidence that Hong Kong will enhance its status as an international aviation hub,” he said.